VI

1. VI5 Moving to V from above.

a. Although VI is used quite frequently as an interior intermediate harmony that leads to another intermediate harmony, it can serve as the final intermediate harmony leading directly to V. When it does so, the ^6 of the VI5 resolves down to the ^5 of V.

b. In minor, one must be careful to avoid doubling the lowered ^6. In order to avoid Parallel 8vas from ^6-^5 a doulbed ^6 would require an awkward leap of an A2.

IV6

2. Phrygian Cadence

a. Like the relationship between II6 & IV, IV6 and VI share two common tones and can be used in very similar situations.

b. In minor, the appearance of a IV6 immediately prior to a V is called a Phrygian cadence. Like the VI in minor, one must be very careful of ¶8va, 5th and Aug 2nds. Thus its a good idea to double the chordal 3rd.

Supertonic Seventh Chords

3. II6/5

a. Much like the Cad64 where the dissonant ^1 resolves down to the L.T., the II65 presents ^1 as a dissonance which can not be the goal of motion but must also resolves to the LT. As well, given its tendancy to grow from a suspension, like the Cad64, it tends to fall on a relatively stronger beat than the V to which it resolves.

b. Since the 7th of the II65 contains a dissonance which strongly pulls us to the LT, it has a richer and somewhat more pronounced function as an intermediary harmony moving to V. As such, if you want to soften the cadential effect of this movement, you may want to consider a II6 instead of the II65.

c. H&VL presents a noteworthy discussion of the soprano voice in progressions containing II65. The most critical thing to watch here is the resolution of that dissonant chordal 7th. Since the ^1 (chordal 7th) resolves to the LT, you must watch carefully to avoid doubling the leading tone.

4. II7 Expanding Supertonic Harmony

a. Just as II6 and II can be interchanged to expand intermediary harmonies so too can II6 (65) and II7

b. Just as 16 can be used as a "PI6" between II and II6 or between II6 and II, so too can it be used between II7 and II65 or between II65 and II7

5. Noncadential uses of II7 and II65

a. Just as the V chord need not always be cadential, movements to V from II7 and II65 need not be cadential. Of particular mention is II65-V42 which share a common bass tone ^4 (remember: The V42 leads to I6 thus softening any cadential effect of the I chord.

6. Other inversions of II7

a. II4/2: Since this inversion carries the ^1 as its bass tone, it is particularly useful as an immediate expansion of tonic harmony. The resolution of the dissonant ^1 yields a V6 or V65.

b. II4/3: Since this inversion carries the ^6 as its bass tone, it is particularly useful as a predecessor to V(7) and Cad 64 as the ^6 will lead down to ^5

Subdominant Seventh Chords

7. IV7

a. We have already seen that the intermediary harmonies II, II6 and IV are very closely related. As intermediary harmonies, they lead away from I and towards V. Similarly there is a close harmonic and functional connection between II7, II6/5 and IV7.

b. Since the II7 (65) contains the ^1 it can only be differentiated from the IV by the existense of its fundamental ^2. As well, the most distinguishing tone in the IV7 is the ^3, the chordal 7th. This tone is not present in any form of II we have seen. Thus the placement and function of the ^3 in the IV is critical.

c. Like the II7 and II65, the IV7 can appear on a weaker beat than the V to which it moves but it is more characteristic for it to occur on a relatively strong beat.

d. Because the progression IV7-V contains a dissonant ^3 that will lead to ^2 and a ^6 that under other circumstances would tend to move to ^5, the voice leading is somewhat anomalous as we must move by leap away from ^6. Moving from ^6 to ^5 would yield P5ths and moving from ^6 to LT ^7 could yield a doubled LT.

8. Inversions of IV7

a. IV65 is the most useful inversion of IV7. When leading to V or V7(inv) the dissonant ^3 of IV65 will lead down to ^2 as we have seen. Thus to avoid P5, the ^6 bass of the IV65 can not lead down to ^5 bass of V(7) and thus will most likely lead to V6 or V65

IN CLASS

9. Plagal Cadences

a. When IV-I is used as a cadential element, it is called a Plagal Cadence.

b. Since the IV does not contain the LT, this type of cadence has a much more limited cadential effect.

10. Deceptive Cadence

a. If a substitution of VI occurs where a cadence is expected, we call the progression a deceptive cadence. Since the VI chord also serves as an intermediary harmony, the use of the deceptive cadence can, in turn, lead to an expansion of intermediary harmony thereby delaying and creating a hightened sense of anticipation of the cadential effect.

11. IV6 & VI

a. Since IV6 and VI are so closely related, we sometimes see the IV6 substitute for VI in a deceptive cadence. In other words, the IV6 substitutes for the VI which, in turn, substitues for the I

b. Similarly, we sometimes see VI substitute for IV6 in the plagally oriented progressiom I-IV6-I6

Tonicization & Modulation

12. Tonicizing V in Major

a. As you might expect, the force of the harmonic series comes into play and the Dominant V becomes a very frequent area of tonicization and modulation in Major. In Minor, the existance of the lowered ^6 creates a pull towards III as the new tonic.

13. Applied Chords

a. H&VL is a little obscure here. The idea is that any major or minor triad can be preceded by its own functional dominant (V or Vii). Such a preceding chord intensifies the non-tonic chord and is called an applied dominant. The target of the applied dominant will, at the minimum acquire the color of a tonic triad.

14. ^+4 as leading tone to V

a. We have seen that an extremely strong elements of the V chord is the LT. In fact, it has such a strong pull that we have required that its half step relationship to the tonic be maintained in minor by raising the ^7 of natural minor and insisting that we never double the LT for fear of forcing ¶8. When we use an applied dominant to the V chord we therefore must create the leading tone to the V chord in the applied dominant. Thus all applied dominants to V will contain a ^+4 that acts as a LT and can not be doubled.

15. The Pivot Chord

a. One way to get a smooth transition between tonal areas within a modulation is to precede the applied dominant with a chord that appears - unaltered- in both the original key and the key to which you modulate. For example, in the key of C the I and VI chords are the same exact spelling as the IV and II chords in the Dominant key of G.

16. III in smaller contexts

a. Another point of clarification in H&VL is the use of III immediately following I. We have seen that III functions commonly as an inner harmony within an intermediate progression. We have also stated that the similarity between III and I (two common tones) results in the progression I-III sounding more like an expansion of I than a movement to III. However one very important use of III immediately following I is to support a decending ^8-^7-^6 line. In this context the ^7 provides stability above the ^3 of the III. This stability and the resultant voice leading cuases the ^7 to appear not as a leading tone to ^1 but rather a passing tone to ^6

17. III moving to I through an inversion of V7

a. H&VL is a little obscure here. In section 15-1 we saw that III moves to V via a passing bass in a II6 or IV. Here H&VL says that III moves to I through an inversion of V(7). As well, by their own admission, H&VL states that III does not move to and from I because the two common tones dont allow the voice leading to sound like a progression as much as it sounds like an expansion of I. THUS: FOR NOW - III DOES NOT USUALLY MOVE TO I. IT MOVES TO V. In addition to moving to II6 and IV and then onto V, III can move directly to V43 or V42 with a stepwise bass.

18. Natural VII leading to V

a. Since the two upper tones of VII also belong to V7, the ^7 in minor need only be raised a half step to be absorbed completely into a V7. As a result, in minor, we sometimes see V7 (inversions) immediately follow VII. One particularly noteworthy voice leading is VII-V65-I which allows for a chromatic rise in the bass to I.

b. In minor, since the bass tone of VII is not a LT, it may fall to the ^6. Most often this occurs with the progression VII-IV6 (II65)-V7

19. VII5 in Major and raised VII5 in minor

a. For now, avoid all root position LT VII chords.

Progressions by 5ths and 3rds

20. Principle of descending 5ths :

a. We have seen repeatedly the gravitational force of the P5 as well as the dim5. When such force is applied to a descending bass line the resultant progression by 5ths becomes: I-IV-Vii-III-VI-II-V-I. In order to avoid a bass line that might proceed to an unruly regiter, we sometimes invert the bass to rise an ascending 4th instead of falling a descending 5th. It is worth nothing that in the above progression, the further the bass drifts from the tonic, the weaker the immediate relation to that tonic.

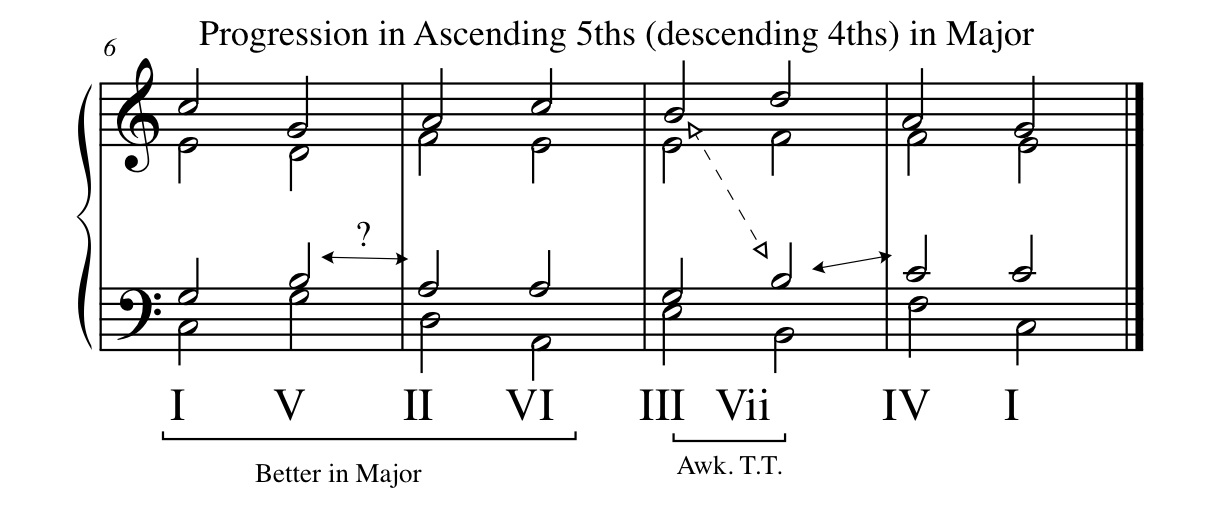

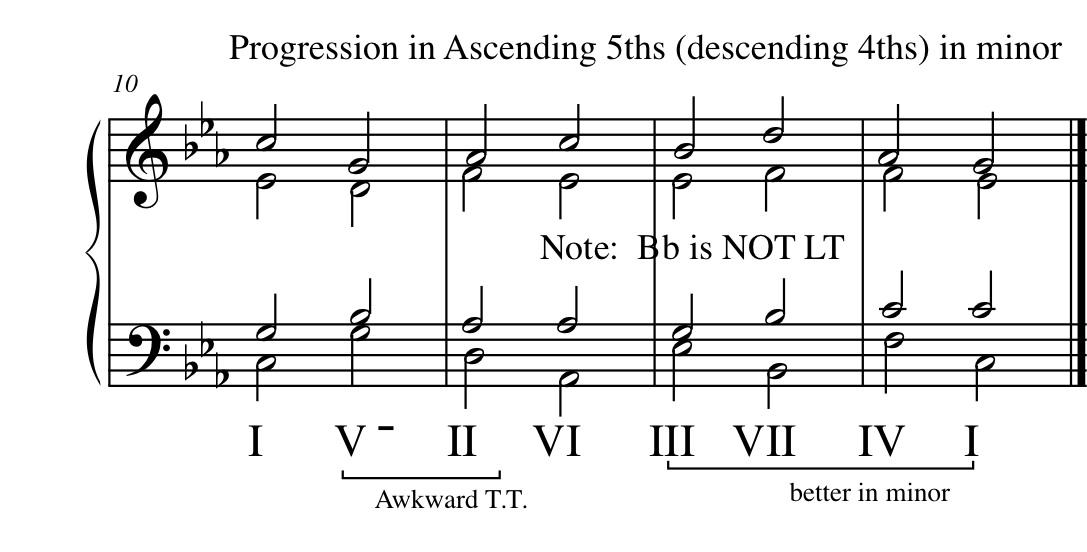

21. Principle of ascending 5ths

a. Partially due to the nature of the harmonic series where the 2nd order ascending 5th takes us significantly out of the harmonic series, progressions by ascending 5ths are much less convincing. As such I-V-II-VI-III-VII-IV-I is rare. H&VL makes a very strong statement that the complete progression is "useless". For sure it is problematic because the placement of the tritone creates weak voice leading. However, with some modal mixture (Using both Major and minor) Portions of this progression can be found such as I-V-II-VI-III in major and III-VII-IV-I in minor.

V as a Minor Triad

22. V without a LT

a. Because V- does not contain a LT it does not gravitate actively to 1

23. Minor V supporting -^7

a. A quick review of Theory2 notes 05 reminds us that in natural minor, VII contains a -^7 scale degree and can thus move to V by raising the -^7 to make it a LT or to IV6 (VI) by lowering the -^7 to ^6.

b. Similarly, in minor the V- can support a -^7 as a motion to VI (IV6). Remember the 7th scale degree must be lowered (and thus not a LT) or else it will naturally gravitate towards ^1

24. Choosing betweeen major and minor

a. Sometimes V- is used simply becuase the color of a minor V is preferred over the typical LT V

25. Minor V leading to tonicized III

a. H&VL sort of skirts around the issue here. Look at minor. We know from Theory2 notes 05 that the modulatory tendancy in minor is towards III due to the natural placement of the tritone in minor between ^2 and ^6. We have seen that smooth modulations can be achieved by using a "Pivot" chord just prior to the applied dominant. We know that the pivot chord must occur naturally in both the original key and the key to which we modulate. Now look at the V-. It exists naturally in the key of III and therefore serves as an excellent Pivot chord to a tonicized III

Sequences with Decending 5ths

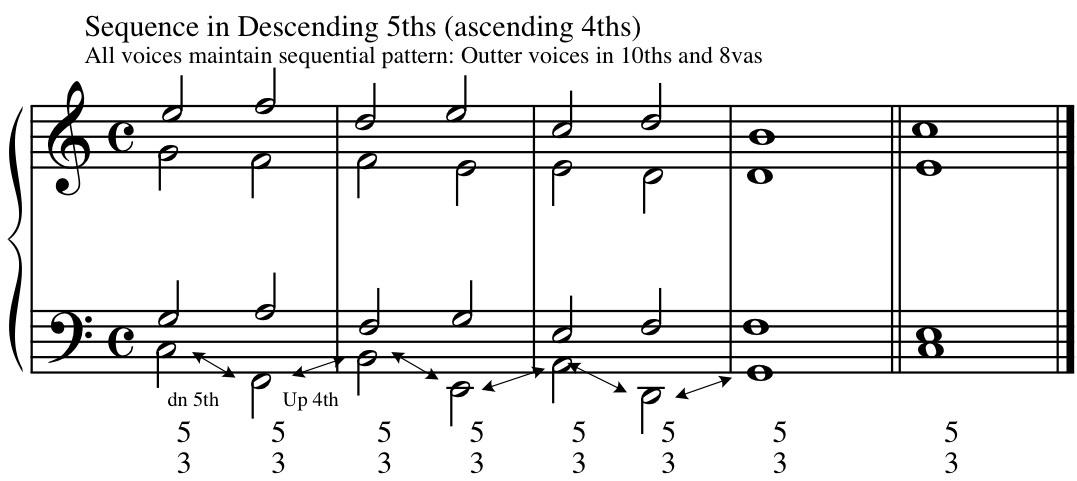

26. Harmonic and contrapuntal implications

a. We saw in chapter 16 that we could build a 53 progression around a bass line descending in 5ths (or rising in 4ths). This sequence will often move its bass in patterns such as down 5th-up 4th or visa versa and may contain a consistant relationship with the other voices.

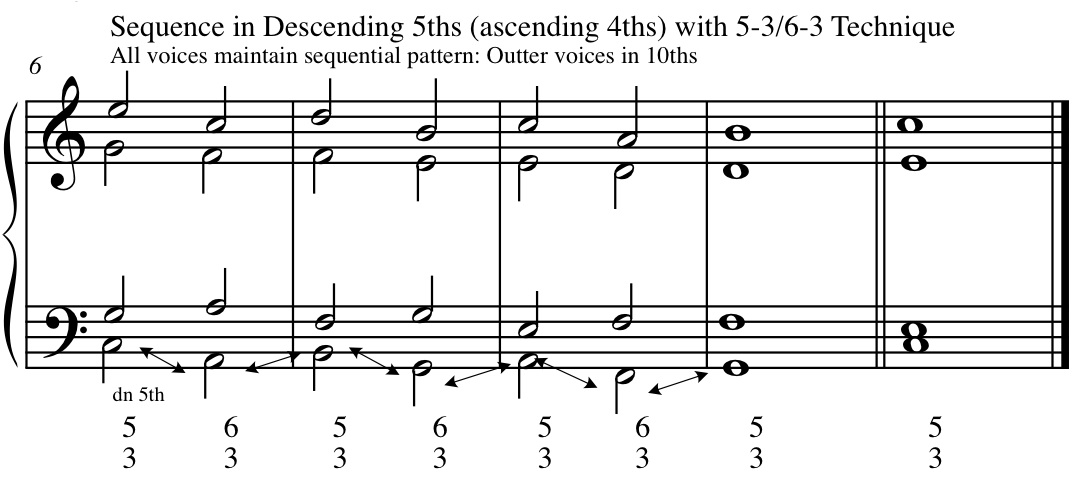

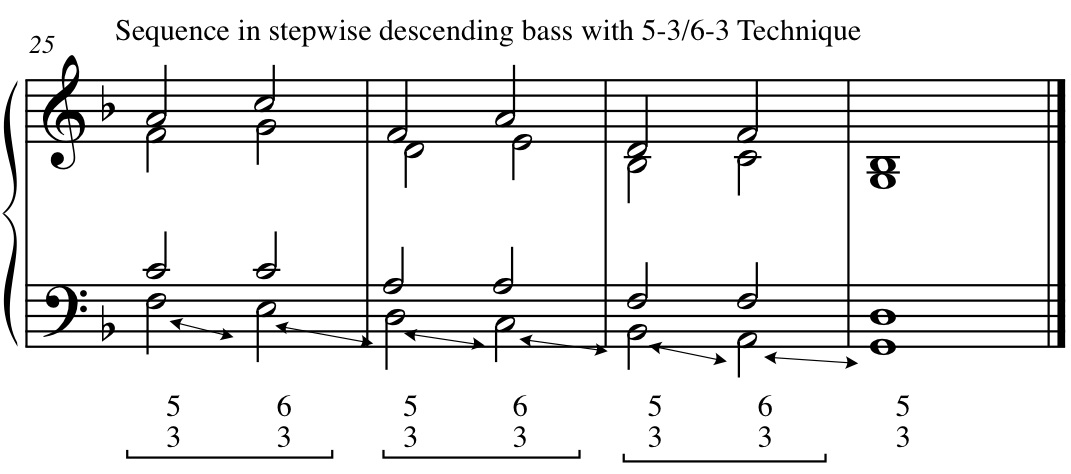

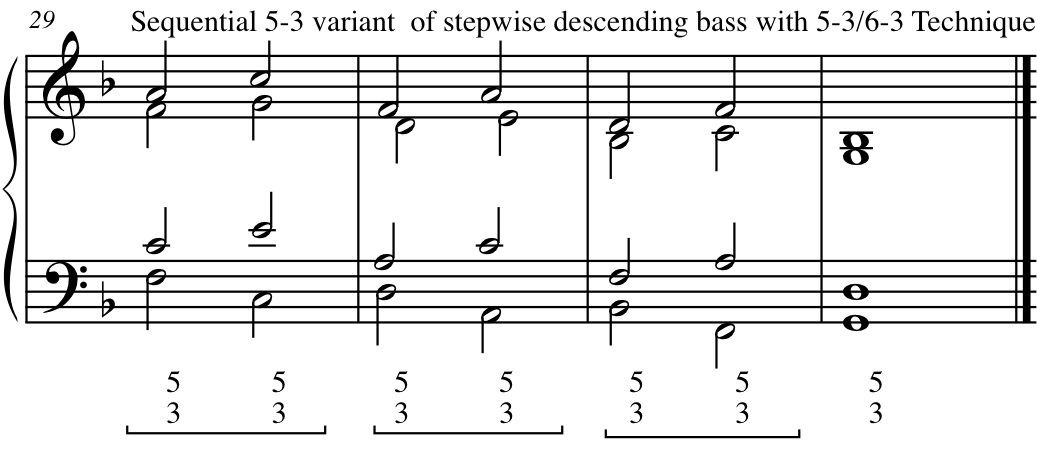

27. 5-3/6-3 pattern

a. If we take our decending 5th sequence above and modify the every other shord so it appears as a 6-3 instead of a 5-3 we derive an alternative to the descending 5-3 in 5ths sequence. This sequence adds additional interest and harmonic variety to the common descending 5ths sequence. One may easily reverse the sequenctial pattern and begin on a 6-3 and alternating with 5-3.

Sequences with Ascending 5ths

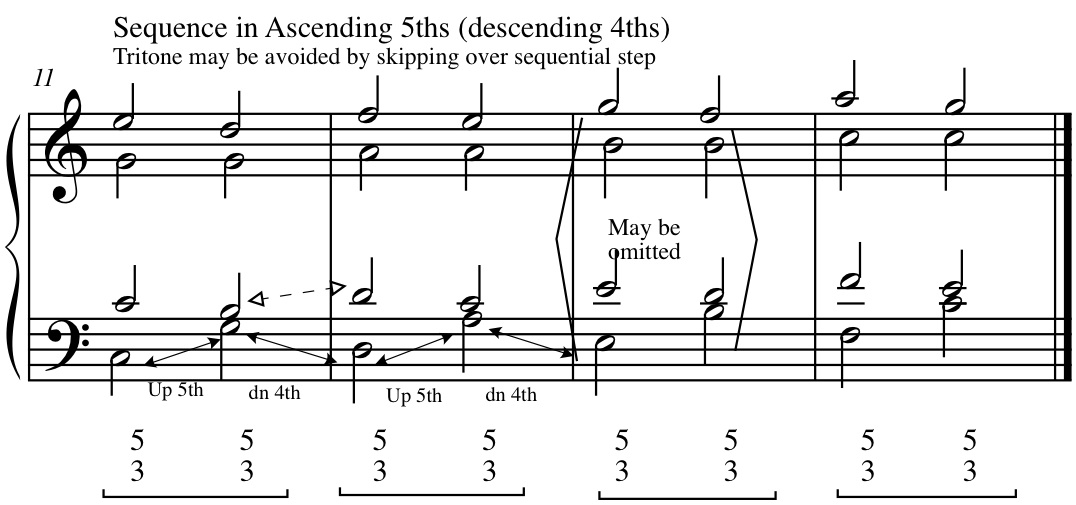

28. Harmonic and contrapuntal implications

a. Like the descending 5th sequence, The Ascending 5ths sequence is created from the same logic we saw in the usage of ascending 5ths in a 5-3 progression. (Review webnotes 06). In the case of a sequential passage of ascending 5ths each pair of chords often supports a soprano line that descends by step.

29. Omitting a step in the ascent.

a. Like the progression in 5-3 position, the sequence of Ascending 5ths has a rather stark tritone between ^7-^4 (VII) in Major and ^2-^6 (II) in minor. Often we see composers simply skipping over these sequential steps thereby avoiding the unwanted tritone.

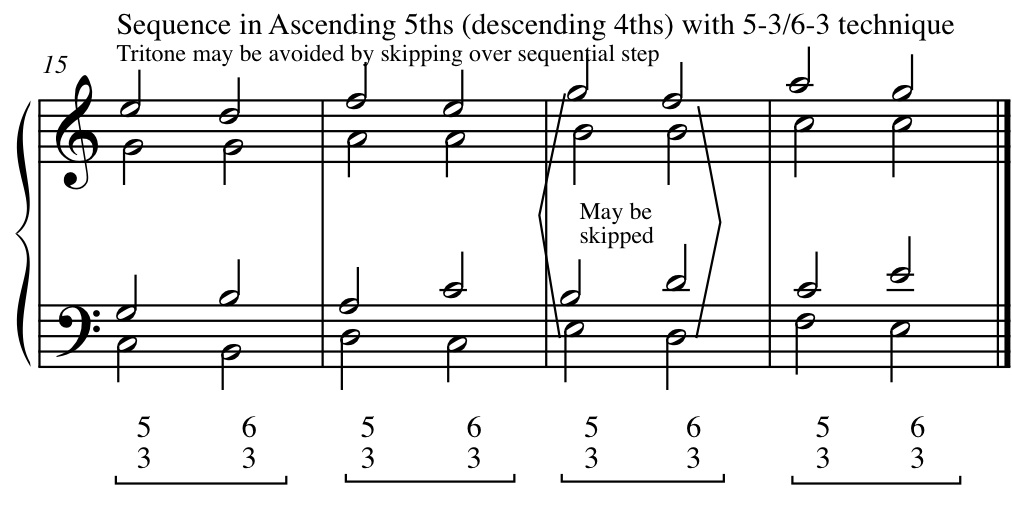

30. 5-3/6/3.

a. As with decending 5ths, an ascending 5ths sequence may have a 5-3/6-3 or 6-3/5-3 variant. Like the 5-3 progression, the 5-3/6-3 variant will sometimes skip the sequential step containing the tritone.

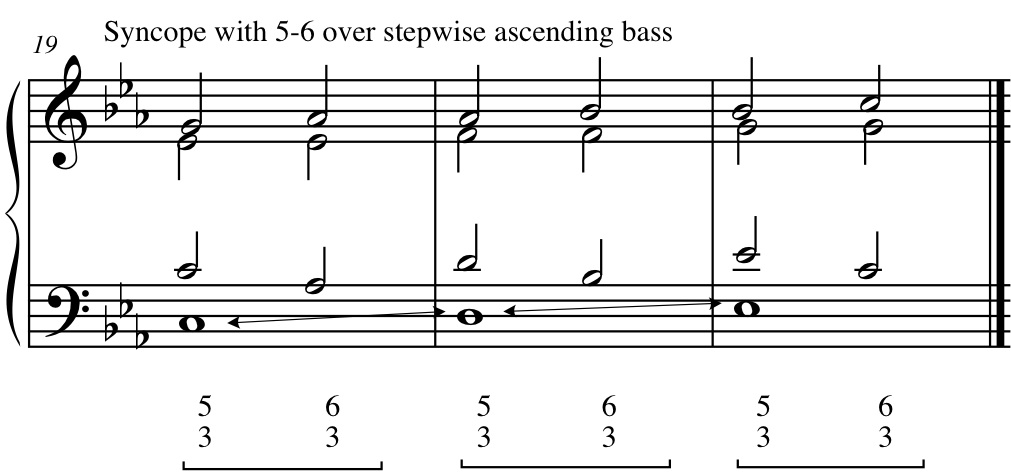

31. Syncopes

a. At various times throughout the year, we have seen the interrelated use of 5-6 and 6-3 chords. We have seen that most any chord can function similarly in 5-3 or 6-3 position and we have seen that above a given bass, the 5-3 chord is very closely linked to the 6-3 with one often substitiuting for the other (remember the use of IV and II6) We can further elaborate on the concept of 5-3/6-3 sequences by allowing the free sequential movement between a 5-3 and 6-3 chord over any given bass. When such movement extends over a demonstrated bass pattern, such a progression is sequential.

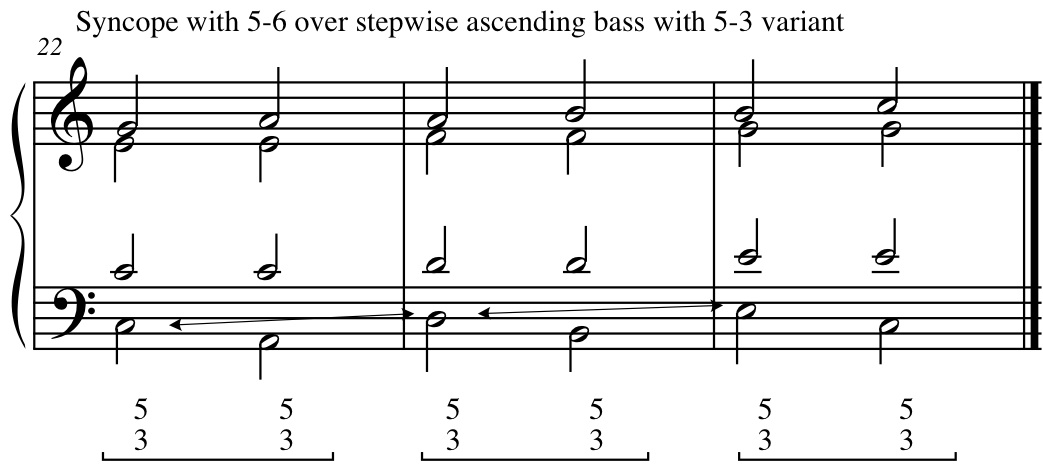

32. 5-3 Variant of ascending 5-6 (syncope)

a. If we transform the 6-3 chords of the Syncope into 5-3 chords over a lowered third bass we get a very interesting root poisition sequential variant of the ascending 5-6 sequence.

Sequences Falling in 3rds (Descending 5-6)

33. Harmonic and Contrapuntal implications

a. When a 5-6 sequence occurs over a bass that descends by step, each sequential segment occurs a third lower than the previous one.

34. Root position variation of descending 5-6

a. If we revoice each occurance of the 6-3 in the Descending 5-6 sequence such that it becomes a 5-3 we get a root position variation of the descending 5-6 sequence.

Less Frequent Sequential Patterns

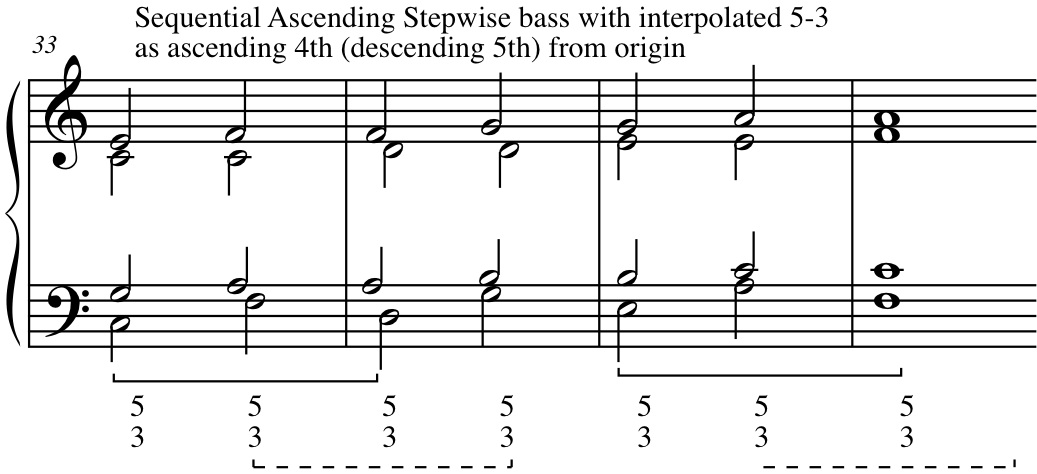

35 Ascending by step with voice-leading 5-3 chords

a. This sequence is built on a stepwise 5-3 bass line. Since such a bass would likely yield problematic voice leading subject to many ¶s, we may interpolate "Voice Leading Chords" (see theory2_notes_06). In this example the voice leading chords are derived as ascending 4ths (descending 5ths) from the origin

36 Syncope with 6-3/5-3 over stepwise descending bass

a. When the interval succession contracts from a 6-3 to a 5-3 over a bass tone we achieve a descending syncope.

Uses of 6-3 Chords

37. Neighboring 6-3

a. We have seen the Vii6 as a neighbor to I and I6 and we have seen V6 as a neighbor or IN to I. H&VL mentions that a neighboring 6-3 works best when the bass is a half step from the origin.

38. Passing 6-3

a. Like the I-Vii6-I6, V-IV6-V6 and II-PI6-II6 progressions, 6-3 most often connects a root position triad with its first inversion. Sometimes we will see an alteration of a passing 6-3 such that it becomes an applied dominant or an applied Vii6 to the target chord. In these cases remember to make sure the temporary LT exists and that the Vii6 appears as a diminished triad.

b. Variations of the Passing 6-3 include connecting two chords whose bass is a 3rd aparat as in the descending 5-6 sequence.

c. Variations of the Passing 6-3 may include a PV6 in the Phrygian cadence (minor) I-PV6-IV6-V. In such cases the ^5 may sustain as a suspension into IV6.

Dissonant 6-4 Chords

39. Three Main Types

a. Although there are numerous uses of of the 6-4 chord, most can be categorized as 1) Accented 6-4s 2) Neighboring 6-4s and 3) Passing 6-4s

40. Accented 6-4 Chords.

a. A quick review of the Cadential 6-4 shows how the chord delays the arrival of the expected dominant V. The 6-4 above the 5th scale degree is heard not as a I chord but more as accented dissonant chord that resolves to V. We have said, in fact, that the chords syntax acts more as a delayed arrival of V than the actual I which it spells.

b. When a dissonant 6-4 chord falls on a strong or accented beat and delays the arrival of an expected melodic or harmonic event, we call that chord an Accented 6-4. In essence, the Accented 6-4 is exactly like a Cadential 6-4 just not part of a cadence. That is, the Accented 6-4 may occur within any proper syntax. Like the Cadential 6-4, it will take on the characteristic of its chord of resolution and should be labeld as such.

c. Voice leading follows the same guidelines as that for the Cad6-4. Double the root in 4 voices to avoid ¶s

d. A word of caution: Try to avoid resolving an Accented 6-4 to a diminished 5-3.

41. Neighboring 6-4 Chords

a. When a 6-4 chord arises from the movement of upper voices to neighbor tones, we get a Neighboring 6-4

b. Like the Cadential 6-4 and the Accented 6-4 the Neighbor 6-4 will typically double the root and resolve the other voices down.

42. Passing 6-4 Chords (above a moving bass)

a. Just as 6-3 chords can be used between a 5-3 chord and the same chord in 6-3 position (visa versa), so too can a 6-4 be used between a 5-3 chord and the same chord in 6-3 position.

b. The passing 6-4 can also expand 7th chords.

c. Passing 6-4 can expand substitution chords like IV6-II6 (instead of IV5)

43. Passing 6-4 above a sustained bass

a. Like the Syncope, a 6-4 chord may appear as a result of movement above a sustained bass. Similar to the passing 6-3, the passing 6-4 will often connect a root position 5-3 to a 6-3 with a bass a step above or below that of the 6-4.

|