Homework: Workbook Chapter 26 or Text Chapter 26 Excercizes #1, 2 4 & 7

In Theory II we saw the use of a pivot chord to prepare an applied dominant. We saw how the forces of the leading tone within a chord lead the ear to a new tonal center (tonic) even if only briefly. The type of voice leading we called tonicization (for a brief moment) or modulation (for a more large scale shift in the tonal center). We will now see that a leading tone chord need not only be applied to the Dominant within the key . As well, since we have seen the close parallel between the V7 (inv) and the Viiº7(inv) and Viiø7 (inv) we will see that we may use any of these chords to lead to new tonal centers.

Modulatory Techniques

1. New goals of modulation

a. In chapter 14 we saw the use of pivot chords to introduce tonicizations and modulations to V as a key area. In unit 15 we saw that in minor, natural VII was an effective pivot through which we could modulate to III. Indeed, in both of these chapters, we had an early introduction to our now familiar applied chords. In this chapter we will expand upon our notion of tonicization and modulation and discover how we can lead to other closely related key areas.

2. Related and remote keys

a. Two keys are closely related if the Tonic of the new key is a diatonic chord in the old key

b. C Major: Closely related keys = Dm, Em, FM, GM, Am

c. C minor: Closely related keys = EbM, Fm, Gm, AbM, BbM

Note: Related keys only differ from the original key by one accidental.

3. Introducing and confirming the new key.

a. Often introduced by a pivot chord (sometimes more than one)

b. The pivot can be any chord that belongs to both keys

b. Confirmed by a cadential progression usually containing some form of II or IV

d. The cadence can include the pivot, it can follow immediately after the pivot, or appear after intervening material.

e. Other techniques such as sequential passages will sometimes form an extended transition between two key areas that do not necessitate a pivot chord.

4. Applications to written work.

a. The most important elelent to modulating well is to understand the diatonic chords in the original key and the key to which you modulate. A chord that is shared by both key areas can function as a pivot and take us smoothly from one key area to the next.

b. As well, a sequence will allow you to eventually modulate to more distant key areas since the syntactic function of the composition will be temporarily suspended.

c. Once you have committed to your pivot and modulation, it is important that you judiciously incorporate the accidentals dictated by the new key area.

d. However, it is not enough to just know how to utilize a pivot and write a decent sequence. H&VL doesnt really focus on the implementation of a modulation so it is important that you look carefully at the example below. As you can see in the example below, the harmonic rhythm and chordal inversions become extremely important. A graceful modulation is often reconfirmed by a cadence in close proximity to the modulation. If the modulation is sublime the first appearance of the new tonic may be a 63 to de-emphasize the tonic until the confirming cadence at which point root position I and V may well appear. Conversely, a sharp modulation written to draw more dramatic attention may not need a strong confirming cadence. In such a case we may find a root position I at the modulation point and a more sublime confirming cadence. In fact, in a few instances in my own writing I have simply let the end of a sequential passage be the modulation without a confirming cadence at all. In such cases the sequence is, in and of itself, a confirmation of its own harmonic motion.

5. New Techniques of Tonicization.

a. We have discussed that the word Tonicization is distinguished from the word Modulation based upon the significance of the new key area in the scope of the composition. A piece that momentarily flirts with a new key area but does not establish that key area as significant in the form of the composition is thought to be a Tonicization. A piece that clearly moves to a new tonic that is confirmed by repeated cadences to that tonic such that the new tonic area becomes a structural element of the composition is considered to be a modulation.

b. There can be a middle ground between tonicization and modulation where small progressions which may include cadential material in a related key may be more substantial than a mere tonicization but not significant enough of a movement to a new key area to be considered a modulation. (see example below)

c. Sometimes a series of tonicized chords forms a sequence or becomes an integral part of a sequence (see above example)

6. Transient Modulation

a. We have stated that the middle ground between a tonicization and modulation can create a sense of a new key area even without the structural significance of a full scale modulation. When such a middle ground modulatiory passage occurs as a part of a larger, full scale sturctural modulation we sometimes refer to that middle ground as a "transient modulation"

Modulation, Large-Scale Motion and Form

7. Tonal Plan

a. We have seen that in the course of writing the smallest single phrase to the more elaborate short forms, harmonic progressions play an essentiial role in the character of the piece. In larger forms, modulation takes on a similar structural importance albeit on a much larger, if not sublime way. To be sure the immediate impact of a I chord immediately followed by a V chord is impressive and immediate in its sense of being. We have seen through our written work that a well executed modulation to V as a key area is a comfortable motion towards a related key and, when executed well can be more sublime than the immediate harmonic progression. We saw in my impromptu at the top of this page that two modulations brought us from the key of Cmajor to the key of B B minor. The motion through G to B was smooth and there was nothing disruptive about the manner in which I proceeded to B. However, when one plays the progression CMaj - B min it seems a bit more jarring. To be sure, well written composition utilize large scale forms that modulate between key areas not haphazardly, but with the same care and attention as does the smallest syntactic progression of a single phrase.

8. I-III-V in minor, Modulation to III

a. We have seen how in minor III in a very convenient point of tonicization as it shares the same key signature as the local tonic I. We have also seen that the syntactic function of III is often that of an intermediary intermediate chord often bridging the transition between I and V via the intermediary chords II, IV and VI. We remember that the direct movement I-III-V lacks a bit of individual identity since the I-III share two common tones as do the III-V.It should come as no surprise then that in larger scale forms, the modulation to III is often a point of repose that continue to a modulation to V often through a tonicization or smaller transient intermediate modulation.

Link to Mozart K 457

GRAPHICAL ANALYSIS

As we begin to understand the harmonic function of larger form compositions, it will become useful for us to talk about the larger scale harmonic motion that focuses primarily on the modulatory points and the harmony that leads us to these points. To do so, it will be useful to implement a graphical representation as shown in the above analysis of the Mozart Piano Sonata K457. To be sure not every harmony is represented in the above graph but those harmonies that represent the main structural harmonic content of the piece. In such a graphic system of analysis, the note rhythms do not actually represent specific time values but rather relative temporal and structural importance. Similarly bar lines tend to deliniate structural portions of the composition.Hence the first Bb quarter in the above example represents an applied dominant to the more structurally important modulation to Eb and hence receives the lesser quarter note value.

9. Modulation to III in Major

a. In major, III is not a close relative of I and as such, did not play as important a role as a modulatory destination in major as it did in minor in the classical period. Indeed, with a Major tonic, the modulation to III in minor differs by two accidentals and the modulation to III in major differs by four accidentals. However, as the classical period came to an end and the romantic period emerged, composers began to explore this large scale relationship more.

10. Modulation to minor V

a. A frequent goal of modulation for pieces in minor is the natural V in minor. Since the modulatory key signature will contain one less flat or one additional sharp it is considered a closely related key.

11. Modulation to IV

a. Since the dominant of IV is the tonic chord, modulating to IV in major too early in the piece can disorient the ear and create an ambiguous sence of key. If, however, the tonic has been given ample time to beome firmly established, IV can be an effective modulatory destination.

b. Without a confirming cadence, a temporary tonicization to IV yields a coloristic tonality that can in fact be emplyed early in a piece.

c. Although still infrequent, modulating to IV in minor does not present a problem as the leading tone to IV will require a +^3.

12. Modulation to VI

a. In Major, VI occurs naturally as a minor triad. Modulating to VI as a minor key therefore requires only a +^5 as the LT to VI.

b. In minor, VI occuras naturally as a major triad. Modulating to VI as a Major key is also easy and requires no altered LT. In a V7>VI one will need to -^2 as the chordal 7th.

c. We saw in chapter 11 that an important syntactic function of VI is to lead down by 3rds from I to IV. This same syntactic function can be applied to VI and IV as modulatory destinations in a larger form context.

13. Modulation to II in major

a. We have seen that modulations to II in minor are found most often when coming from a Major key as the II inminor will differ from that of the major key by only one accidental.

b. Other types of modulations to II (from major to major, from minor to major and from minor to minor) are not closely related and occur much less frequently.

c. In general, when II arrives as the destination of a modulation it often is a transitionary point for a further modulation to V

14. Modulation to VII in minor

a. Although closely related, VII in minor is more often found as a point of tonicization or transient modulation than a structural modulation.

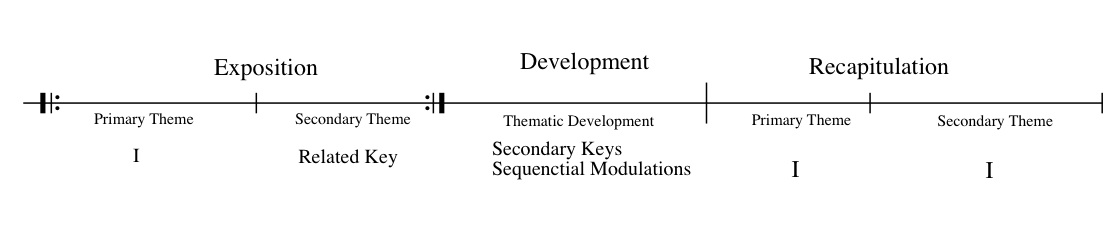

NOTE ABOUT SONATA ALLEGRO FORM

a. H&VL makes a quick reference to the Sonata Allegro Form on page 460. H&VL states that a modulation to VI is sometimes found as the destination of the 2nd part (subordinate theme) in the exposition of a Sonata Allegro form and that, like its syntactic function, it leads structurally to a modulation to IV on its way through the development section. The graph in H&VL is somewhat misleading and the modulatory destinations can be any closely related key (as music evolved, these destinations also become more remote) A more general graph of the Sonata Allegro form is below:

15. Modulations within a prolonged dominant

a. We have seen that V is a very common modulatory destination. When the modulation to V forms part of a large structural form, one may encounter subordinate modulations that return not to the original tonic but to the V

b. In general, any structural modulation may have subordinate modulations which help to define the over structure.

16. Large Scale Expansion of Contrapuntal Chords

a. H&VL simply states here that in the classical period we would often see syntactic progression take on a larger scale harmonic function. It should be noted that much of the way our ear perceives syntactic progression is due to the inherant voice leading between two chords. Such detail is obscured in the perception of large scale tonality.

|