I, V and Vii all are integral parts of cadential harmonies. We have seen with the use of inversions of V, I and Vii that we can expand these harmonies and thus broaden our tonal vocabulary. In this chapter we will continue to exapnd our hamonic palate by moving beyond basic cadential functions.

Homework: Workbook Chapter 9 Pg 61 all, pg 62#1, pg 65#4 (give complete Roman and arabic numeral analysis)

Intermediary Harmonies

1. Moving to the Dominant

a. We have seen that inversions of Cadential chords I, V and Vii can be used to expand basic harmonic progressions. We now will explore those harmonies that are not part of the cadential progression but rather connect the cadential progressions as a further expansion of our basic harmonic progressions. These additional harmonies are known as intermediary harmonies. Among the most important are the II chord and the IV chord. Since these chords contain the 2,4 & 6th scale degrees they tend to be more active (less stable) than 1,3,5 scale degrees of the I chord and thus propell us away from I and towards V.

2. Cadential Uses

a. IV and II create an expansion away from I by either forming part of a cadential progression towards V or a non cadential progression leading towards V. "Direct" cadential progression tend to lead towards root position V while non-cadential progressions tend to lead within expansions of inverted I & V

3. Subdominant harmony.

a. Just as I and V have a special connection due to the root position bass movment of a P5, so to does I and IV. Since IV and V share no common tones, one must use extreme caution to avoid Parallel 5th when leading from IV to V. Frequently, the bass tone of a IV-V progression moves in contrary motion to the upper voices.

4. Supertonic harmony

a. II and V also have a root position bass movement of a P5 and therefore have a special connection. As well, I and II share no common tones so one must use extreme caution to avoid Parallel 5th when leading to II from I. It is generally a good idea (although not the only idea) to allow the bass tone of a I-II progression to move in contrary motion to the upper voices.

{insert inclass #1}

5. II6

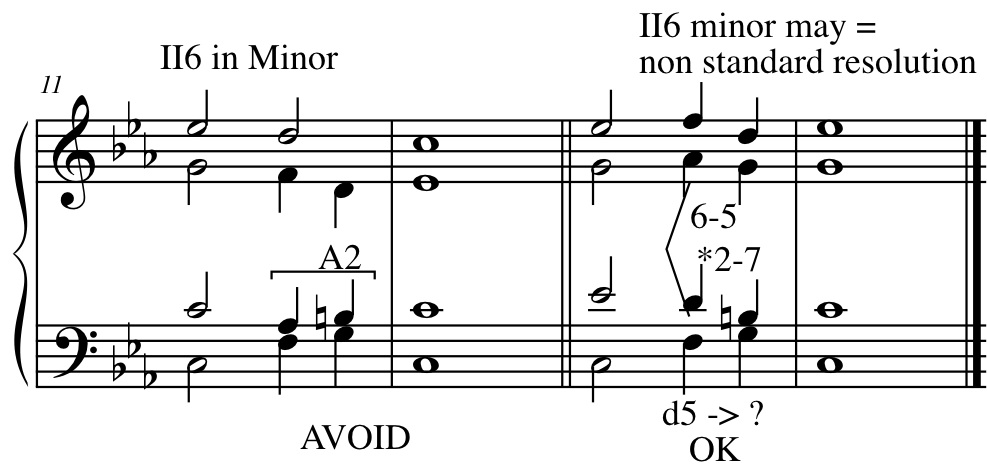

a. In Major both II and II6 move quite easily. In minor, the lowered 6th scale degree creates a diminished triad on II. Like the dimVii6 in Major, the dim II6 satisfactorily leads to V in minor. For now, we will avoid root position II in minor.

b. Since, in minor II6 contains the lowered 6th scale degree and V must contain the raised 7th, leading from II6 to V with the lowered 6th moving to the Leading tone creates an unwanted A2nd. Avoid.

c. The II6 in minor contains the tritone between the 2nd and 6th scale degree. To avoid the aforementioned A2nd the 6th scale degree often resolves to 5. However, since the V chord does not contain the 3rd scale degree, the 2nd scale degree of the II6 cannot ascend to 3. As a result II6-V will often contain a d5 moving to a P5.

d. As an intermediary allowing V7 to fall to 16 via V4-2 (remember V7-16 should be avoided as it results in hidden octaves

{insert II6 minor}

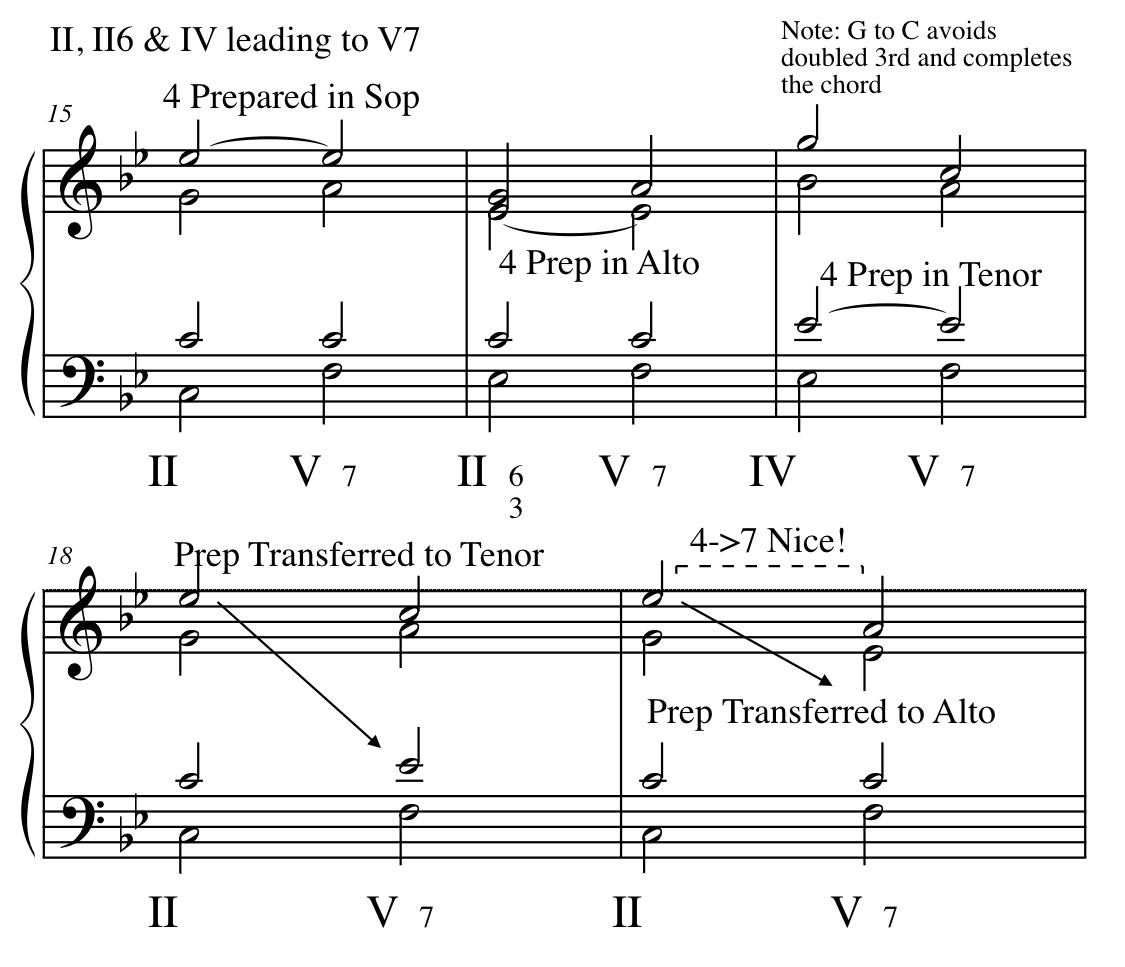

6. Moving to V7

a. IV II and II6 all move well to V7. In fact they all share the 4th scale degree. When this 4th scale degree is present in the same voice in the IV, or II or II6 chord AND in the V7, the dissonance in the V7 is said to be "prepared", Throughout our study of harmony, we will see many benefits to preparing dissonances. When the preparation of the dissonance occurs on a strong beat the preparation is called a "suspension". The strength of the prepared 7th is significant and, at times can warrant its doubling.

7. I6 leading to IV or II6

a. We have seen that I6 is an expansion of the same tonic harmony as I. Since the role of II, II6 and IV is to lead away from I and towards V, these chords work very well in progression with I6. In addition the 3rd scale degree of the bass I6 lies just a step away from II6 and IV creating very smooth voice leading. Since this bass is just a step away, be very careful of parallel octaves.

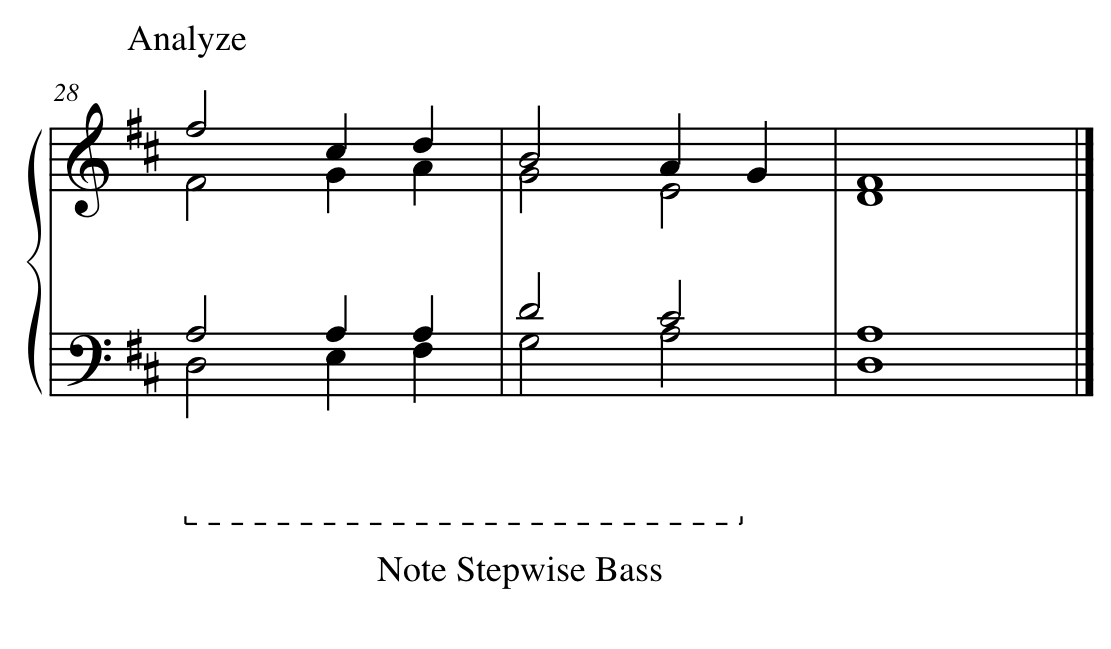

8. Connecting I and V by stepwise bass

a. With the addition of the 4th scale degree that does not represent a dissonance and can rise (remember V4-2 will have a 4th scale degree that falls to I6) we can now harmonize an ascending bass line. Note that V43 or Vii6 can be used to bridge I and I6

{insert analyze}

IV and II in Contrapuntal Progressions

9. Moving to Vii6, V6 and inversions of V7

a.II, II6 and IV can all move easilyt o Vii6, V, V7 and its inversions. Of particular mention is II6 and/or IV moving to V4-2. Since all of these chords contain the 4th scale degree in the bass, such voice leading allows the bass to remain stationary while the upper voices change the harmonic function of the chord. (Play Mozart ex 9-14)

b.When II6 or IV moves to V63 or V65 there will be a upwards jump of an A4 or a downwards jump of a d5. Since the downwards jump of a d5 to the leading tone will be followed by a stepwise ascent to the tonic, the contrary motion helps to offset the dissonance in the bass line. 10.

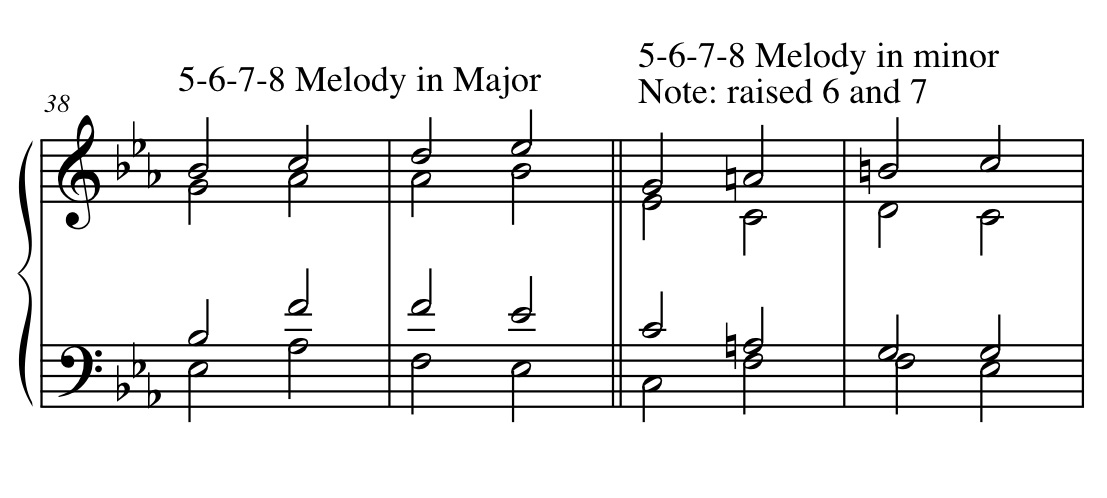

a. With the addition of II, II6 and IV, we can now harmonize the melodic motion ^5,^6,^7,^8. When harmonizing the leading tone^7, avoid the V or V7 chord as they will tend to lead to parallelisms. Instead use Vii6, V43 or V42 (note V6 and V65 would result in doubled leading tones)

Expanion of II and IV

11-13.

a.Just as I and V can be expanded by I6 and V6 (and reverse), so too can II be expanded by II6 (and reverse)

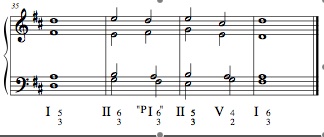

b. Often a "16" will "Pass" between II and II6. This I6 does not serve a cadential function but simplay acts as a bridge to pass from one chord to the next. I will often refer to the "passing I6" as a "PI6"

c. When the ^1st scale degree of the IV5 chord moves to the ^2 scale degree and all other harmony tones remain constant, the resultan harmony becomes a II6. This is called the 5-6 Technique and is the first of many "sequential expansion techniques we will see in the semesters to come.

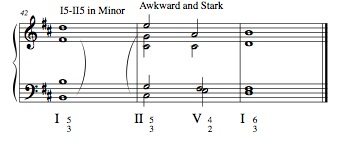

d. In minor the progression I-II can yield very stark voice leading and thus is often avoided. However, when used as an expansion of intermediatry harmonies II6 and IV in minor, it can have a rather nice effect. (see Shubert

Harmonic Syntax: Rhythmic Implications

It is important to note that in real compositions, the rules below are often broken. However, in order to understand and justify such exceptions we will stick to them for now.

14 Harmonic Syntax

a. Bass tones of V6, Vii6 and inversions of V7 must lead by step to I or I6 (unless part of an arpeggiation that expands V or V7)

b. Intermediate Harmonies move away from I and towards V, V6, Vii6 or V7 (+inversions) They never follow these chords.

c. Intermediate Harmonies never lead to I

d. Intermediate Harmonies can expand upon themselves.

15 Chord Progressions and Rhythm

a. Dont repeat a chord from a weak beat to a strong one

b. Dont repeat a bass note from a weak beat to a strong one (ie IV-II6) except when the bass functions as a suspension (ie II6 to V42)

16 Subordinate Progressions

a. Since we now can expand 1-V with intermediary harmonies, the aggregate expansion can itself be throught of as a smaller, more localized representation of I or V which can, in turn be expanded. This will become a critical element in the study of musical form. If the localized expansion sounds too cadential, avoid root position I and V.

|