Homework: Workbook Ed 3 Chapter 15: Preliminaries

pg 121 a, e, g Preliminaries pg 122 c,d,h Pg 123#2,

126 #2 127#3, 128#3 130#6

Homework: Workbook Ed 4 Chapter 16:

pg 133-137 all, 139#3, 140#s 1,23

ABOUT THE MIDTERM:

The

first partof the midterm will be a take home writing assignement in

which you will compose a short passage based on specified

criterion. You may see and download the midterm on

the webnotes.

The second part will be an in-class second species counterpoint

All homework

assignments will be due the day of the

midterm.

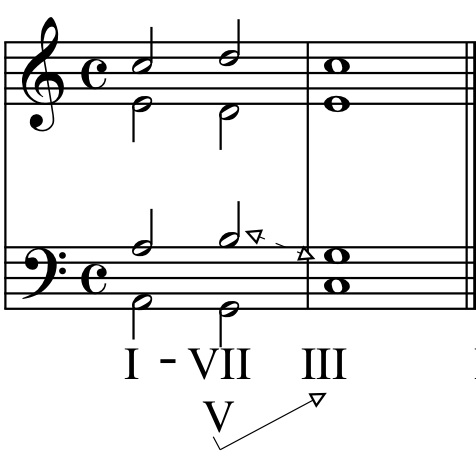

Uses of III

1. I-III-V in minor :

a. Since III shares two tones with I (^3 & ^5) a direct progression

from I to III sometimes sounds like nothing more than an expansion of

I. This is particularly true when the chordal 5th (^7) is missing

from the III. As a result we see that the progression I-III-V

seldom occures in direct succession in the classical period.

However, the direct progression I-III occurs rather frequently after

that period and is a particularly effective way to evoke a modal change

within a progression (ie change from minor to major or major to

minor) and is often used in music for media.

b. However, since the progression I-III-V outlines the tonic triad in

the bass, its use as an outline of harmony is valuable. In minor we

often move from I to II via - VII (remember I use - instead of b to

indicate a lowered tone... thus in C minor the "-VII" is a Bb Major

triad). As you can see, the VII in minor can act as an applied dominant

to III. Similarly the II6 in minor can act as the applied Vii6 to III.

|