Homework: Workbook Chapter 16 p131#1a,d,e //132#2 a,b,e// 136#2,3

Homework: Workbook Ed 4 Chapter 17: pg 143-144 a,c,e,g, 148#3, 149#4

BRAVO!:

You have now completed the first phase of a more enlightened understanding of the function and implementation of triadic harmony and voice leading in the classical context of western music. We now begin to examine how the techniques we have learned over the past 8 months can be further expanded. With the exception of our continued study of species counterpoint, our focus will shift from the rules of harmony and voice leading to the creative implementation of these rules. Our solid arrows have shown me that you understand the rules and our dashed arrows have allowed me to show you that when well conceived, a rule may be superceded. It is now your turn to show me some dashed arrows!

Progressions by 5ths and 3rds

1. Principle of descending 5ths :

a. We have seen repeatedly the gravitational force of the P5 as well as the dim5. When such force is applied to a descending bass line the resultant progression by 5ths becomes: I-IV-Vii-III-VI-II-V-I. In order to avoid a bass line that might proceed to an unruly regiter, we sometimes invert the bass to rise an ascending 4th instead of falling a descending 5th. It is worth nothing that in the above progression, the further the bass drifts from the tonic, the weaker the immediate relation to that tonic.

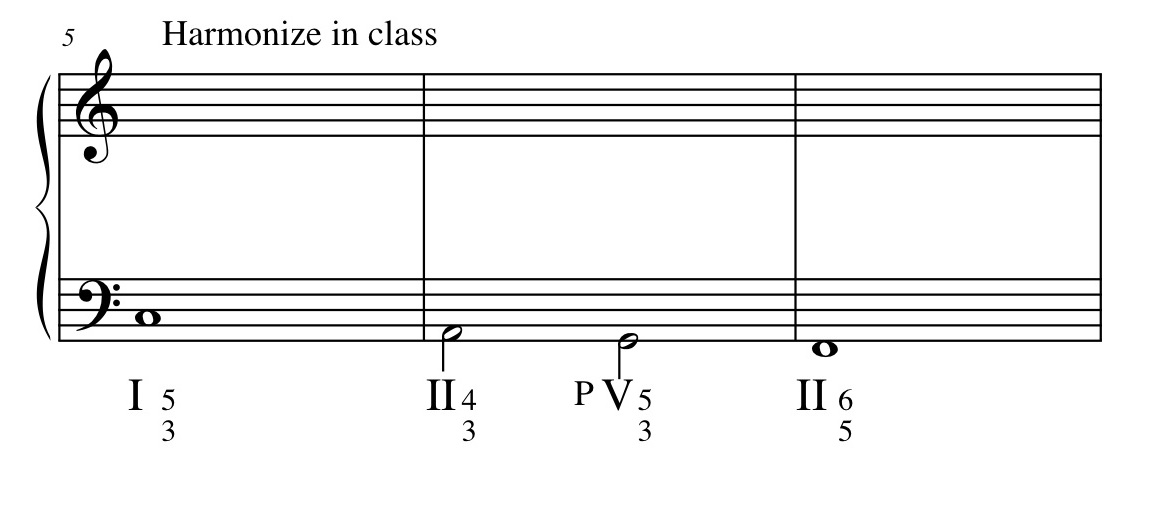

insert 16-1

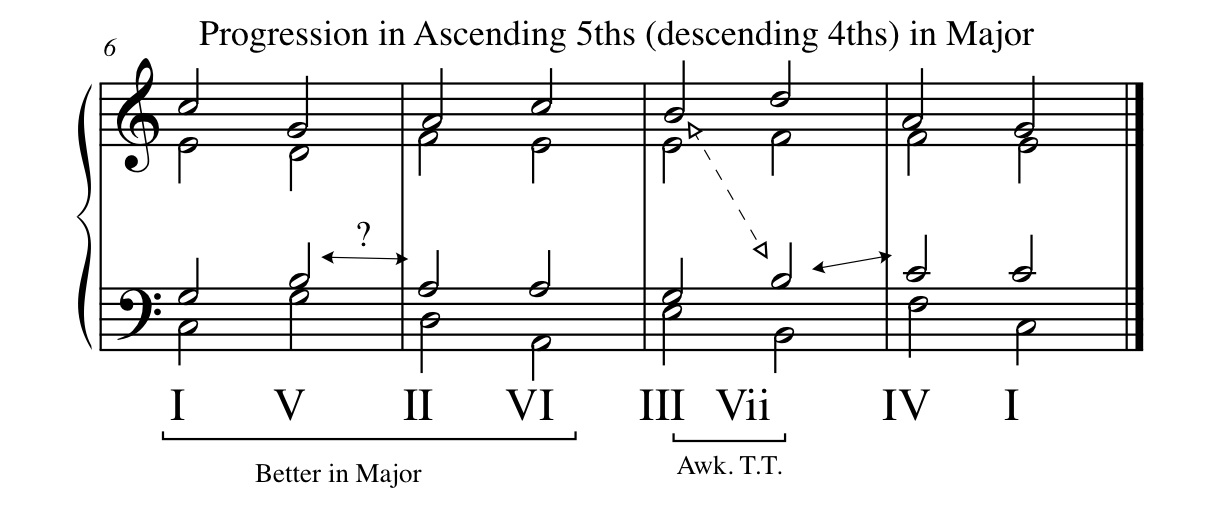

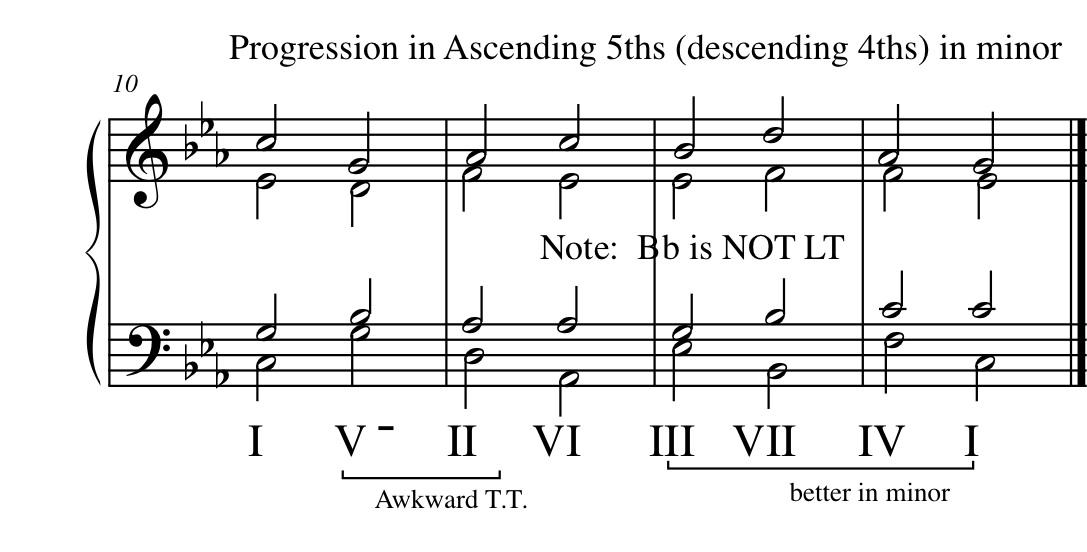

2. Principle of ascending 5ths

a. Partially due to the nature of the harmonic series where the 2nd order ascending 5th takes us significantly out of the harmonic series, progressions by ascending 5ths are much less convincing. As such I-V-II-VI-III-VII-IV-I is rare. H&VL makes a very strong statement that the complete progression is "useless". For sure it is problematic because the placement of the tritone creates weak voice leading. However, with some modal mixture (Using both Major and minor) Portions of this progression can be found such as I-V-II-VI-III in major and III-VII-IV-I in minor.

3. Bass motion by 3rds

a. We have seen that one function of VI is to provide a descending bass motion in 3rds between I and IV (II6) . and we have also seen that an ascending bass motion in 3rds is found in progressions that outline I-III-V

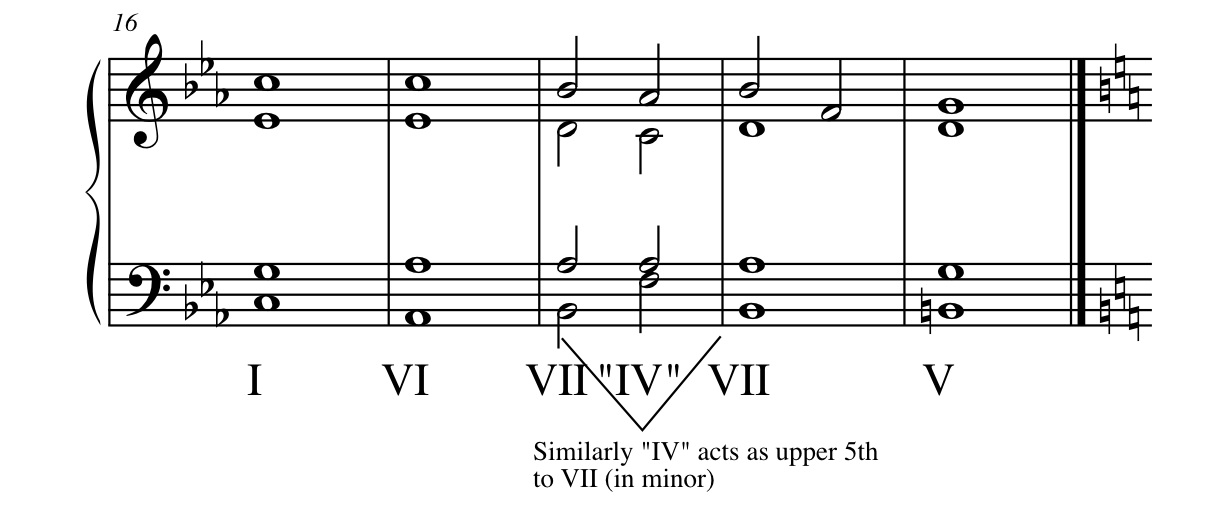

4. 5-3 Chords built on the upper 5th

a. We know that there is a strong progression with any bass that descends by P5. Such is the case with root position progressions V-I, VI-II, VII-III (where VII is an applied dom to III), I-IV and III-VI (where III is an "intermediate" intermediary harmony)

b. Sometimes we see a bass motion that calls on the gravitational strength of the 5th to seemingly contradict some of our rules of voice leading. One such example is the progression I-V-II-V. In this progression the "II" does not act as its usual intermediate function but rather as an expansion of V. With the descending 5th in the bass between II-V and the immediate proximity to V, II acts convincingly as an expansion of V. Another interesting example is VII-IV

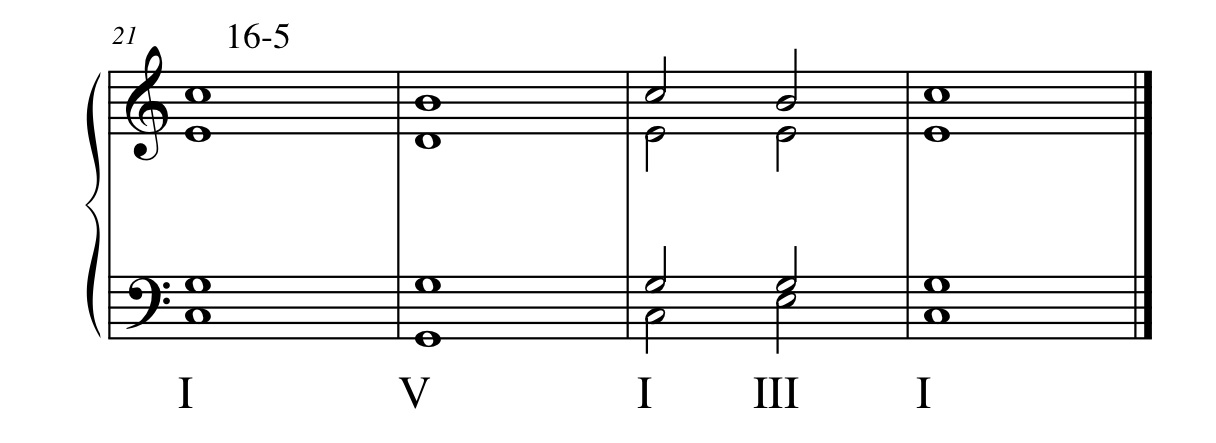

5. 5-3 Chords built on the upper 3rd

a. We have seen that the 6-3 position of many chords can be used as an expansion of the root position of that chord. Some examples have included I6 expanding I, II6 expaning II and V6 expanding V. We have also seen that there is a very close relation between two triads that share at least two tones. Such is the close connection between II6 and IV, IV6 and VI, Vii6 and V, VI and I etc...

b. In the 18th century, composers took these two concepts and sort of merged them yielding progressions built on upper 3rds such as I-III-I and VI-I-VI

6. Contrapuntal Chord Functions

a. H&VL makes an important point in this section: Sometimes, the decision to use a chord is based more in consideration of voice leading than harmony. Often, the chordal usages we have been learning will be employed to prevent poor voice leading. NOTE: This is simply an explanation of how we can conceive of chordal usage in two different ways. For now, you must not randomly insert chords exclusively based on voice leading considerations.

7. 5-3 Chords in support for passing tones

a. Some chords function more as support for passing tones in an upper part than as an independent harmonic entity. We saw the use of the direct progression I-III-IV-I where III supports ^7 in a downward motion to ^6.

b.

Another similar technique is found with a 5-3 descending bass in 3rds supporting a descending stepwise upper voice. In this case, the intermpolation of a chord lying a diatonic step below that to which we are moving creates a support for the passing tones.

c. Look closely at the above example: Is there anything wrong with the syntax? Does the progression make sense according to the rules of harmony we have studied so far? Indeed it does make sense. I-V-VI is a deceptive cadence. VI-III-IV uses III as an intermediate-intermediary harmony. IV-I-II+ is an applied dominant to the last V chord. As such the I acts as the pivot chord (it exists in both the key of C and G) and the I has a plagal cadence relationship with the IV.

This begs a question: When one devises a harmonic concept that works in tandem with good harmonic syntax, which do we hear? Which is the more powerful force? Which governs any subsequent harmony and voice leading? What is your favorite flavor ice cream? The answer to these questions hold the key to the most critical elements of your understanding of harmony and voice leading.

d. Now look again closely at the above example: Is there anything wrong with the voice leading? Look at bar 1. Do you see the unresolved LT? Naughty Naughty! - does the sound bother you? Probably not. Its flows nicely. In this case the idiomatic^7 acts as descending passing tone much like the ^7 in the alto of bar 2. The forces of the smooth descending stepwise melody supported by an interpolated descending 3rd bass are so strong, they overpower the force of the LT-Tonic relationship.

8. 5-3 Chords above a bass passing tone

a. We have seen P16 between II6(IV) and II. We have seen Vii6 between I and I6 and, in general, inversions work better than 53 chords as functional passing harmonies

b. However, 53 does work well as a passing chord between 43 and 65 as it will yield satisfying ¶3 or ¶10

9. 5-3 Chords as support for neighboring tones

a. H&VL states that neighbor tones in upper voices are often supported by a 5-3 bass that is a 5th below the main main chord. Whereas this is interesting, I find this to be simply a restatement of various harmonic concepts we have already dealt with as it provides no new syntax.

b. However, H&VL does point out that in the romantic period we see composers use 5-3 chords to support neighbor tones by dropping the bass a 3rd as in the progression I-VI-I supporting ^5-^6-^5

10. 5-3 Chords above a bass neighbor tone

a. As stated, "does not require much discussion"

V as a Minor Triad

11. V without a LT

a. Because V- does not contain a LT it does not gravitate actively to 1

12. Minor V supporting -^7

a. A quick review of Theory2 notes 05 reminds us that in natural minor, VII contains a -^7 scale degree and can thus move to V by raising the -^7 to make it a LT or to IV6 (VI) by lowering the -^7 to ^6.

b. Similarly, in minor the V- can support a -^7 as a motion to VI (IV6). Remember the 7th scale degree must be lowered (and thus not a LT) or else it will naturally gravitate towards ^1

13. Choosing betweeen major and minor

a. Sometimes V- is used simply becuase the color of a minor V is preferred over the typical LT V

14. Minor V leading to tonicized III

a. H&VL sort of skirts around the issue here. Look at minor. We know from Theory2 notes 05 that the modulatory tendancy in minor is towards III due to the natural placement of the tritone in minor between ^2 and ^6. We have seen that smooth modulations can be achieved by using a "Pivot" chord just prior to the applied dominant. We know that the pivot chord must occur naturally in both the original key and the key to which we modulate. Now look at the V-. It exists naturally in the key of III and therefore serves as an excellent Pivot chord to a tonicized III |