Homework: Workbook Chapter 32

Preliminaries all

Longer Assignments 1

or

Textbook Chapter 30 Preliminaries 1a,b,c,d,e

New

Modulatory Techniques

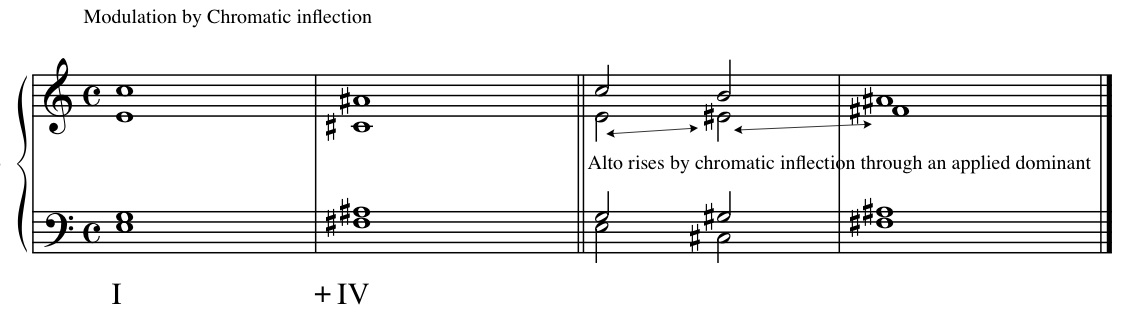

1. Modulation by chormatic inflection

a. When a modulation can not occur through a diatonic pivot, chromatic

inflection can be used to effect a modulation.

b. Often times this will result in an applied dominant to the new key area.

2. Common Tone modulations

a. Sometimes a common tone is all that is provided to carry the listener

from one key to the next.

b. Please note: Common Tone modulations never really seem like modulations

to me. They seem more like tonal shifts. The lack of a leading tone and

the lack of an applied ^5 makes the new key area seem temporary in my ear

until it is confirmed with some more dominant like function. As such I prefer

to call these Common Tone Transitions. For now we will use the nomenclature

given by the book.

3. Modulation by chromatic sequence

a. H&VL simply states here that just as we may modulate via a diatonic sequence

so too can we modulate through a chromatic sequence. Please refer to chapters

31 and earlier for techniques in chromatic sequences.

4. Enharmonic Modulations:

True vs. Notational Enharmonics

a. When a composer spells a passage to make it easier to read (ie respells

bb or X) we consider this simply a notational enharmonic as the syntactic

function of the passage does not change from its origianl spelling.

b. When a composer changes a spelling so that he may reinterpret

its syntactic function we refer to this as a True Enharmonic respelling.

That is, the respelling is true to the syntactic function of the passage.

5. Enharmonic modulation based on the diminished seventh chord

a. An enharmonic reinterpretation of the diminished seventh chord reveals that it may be interpreted as a diminshed seventh applied to 4 different chords.

b. composers may exploit such enharmonic reinterpretations by building an expectation of a movement to one chord or key area than enharmonically reinterpreting the applied viiº chord.

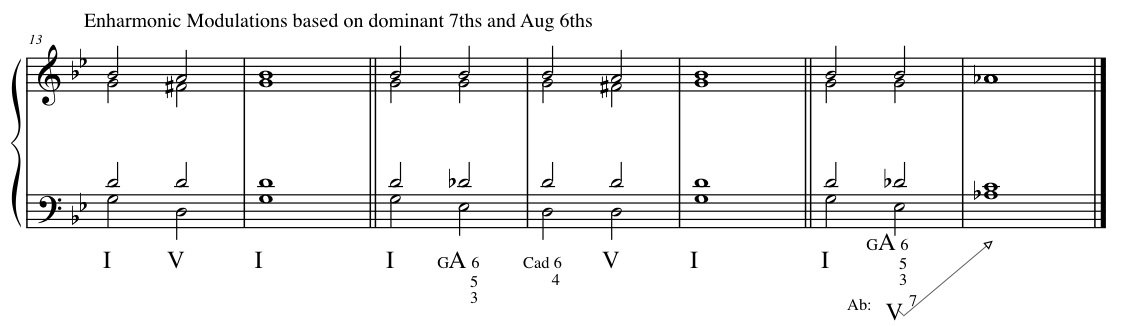

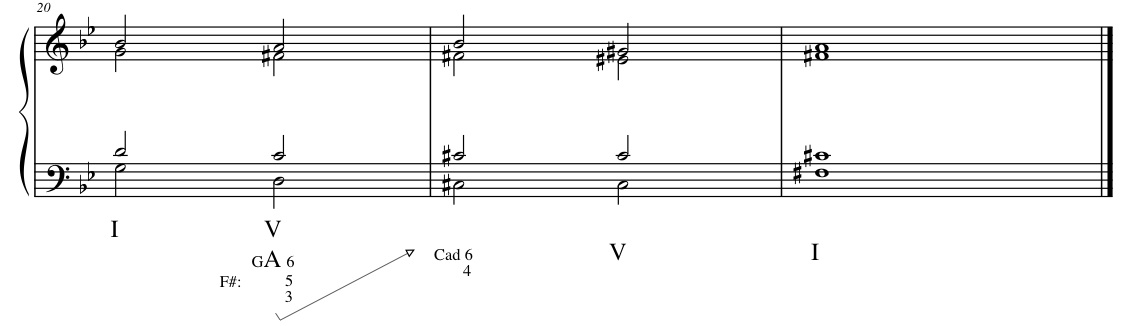

6. Enharmonic modulations based on dominant seventh and Augmented 6th.

a. Since the gA65 may be reinterpreted as an applied V7 we may exploit such ambiguities.

b. Please see webnotes theory4_notes_03.html for additional disscussion.

Chromatic Tonal Areas

7. Large

Scale uses of mixture.

a. Just as chromatically altered triads can be inflected into diatonic progressions,

so too can we introduce mixture into the larger structure of a composition.

8 -VI in major.

a. -VI is one of the most common areas for large scale mixture.

b. It often comes directly from I through common-tone modulation.

c. Sometimes we see it as an expansion of a deceptive cadence.

d. Transforming the -^6 to the root of an A6 chord is an excellent way to return

to the original tonic key.

9. +III in major.

a. Since +III in major contains +^4, +^5, +^1 and +^2 tones not related to I

the modulation to +III is much more delicate.

b. One excellent method of arriving at +III as a tonal area is by transforming

1 into an A6, resolving to a V>III

10. +VI in major.

a. Similar to +III, +VI also contains +^4,+^5 and also conains +^3 and is thus

a more remote key area.

b. Similar to -VI in major, one may arrive at +VI via motion away from a deceptive

cadence.

c. Like the syntactic progression I-VI-IV, +VI in major will often move to

IV as a secondary key area.

11. -III in major.

a. Lowered III in major shares a close connection with the relative minor of

the tonic key. (It is the relative minor!)

b. Like the -VI, it shares a common tone ^5 with I. Thus we sometimes arrive

at -VI as a key area via the introduction of ^5 as a common-tone modulatory

point.

12. Altered Triads in minor.

a. Here H&VL states that it is less common to see modulations on a large scale

from a minor tonic to the minor forms of expanded altered triads.

b. He states that since +^6 and +^7 have strong tendancies towards the original

tonic ^1, it is hard to stableize those chords that may serve as expanded tonal

areas. ie.. +III and +VI in minor.

13. An example of double mixture:

-III- expanded

a. Please refer to webnotes 5 for techniques of modulation to double mixture.

14. #IV as a goal.

a. +IV can not be a result of mixture as it shares no common tones with the

original tonic key.

b. As a result, modulation to +IV is often very difficult.

c. As we have seen in previous discussions, sequential passages can be very

effective as modulatory techniques

d. As well, H&VL very wisely points out that a modulation to a new key area

can and sometimes does occur in two stages. In this case the +IV could be approached

as a modulation to two consecutive keys both a minor 3rd above the preceding

key.

15. Equal divisions of the octave.

a. Sometimes composers will modulate to successive key areas that equally divide

the octave.

b. Thus, we might see modulatory key successions : I,-III, -V, VI(bbVII) (representing

modulations to key areas by minor thirds)

c. or I, -VI, III, I (representing modulations to key areas by descending

major 3rds.

16. Motivic aspects of large scale

chromaticism.

a. As we will see in contemporary theory and composition HMU 420, the smallest

melodic motive can be organically related to the larger syntax and the tonal

order of that syntax can and often is organically related to the large scale

harmonic structure of the piece as a whole.

We have now concluded our study of traditional

tonal harmony. H&VL is a widely accepted standard

text for college music theory and you should

all consider your endurance to complete such

a lofty text a right of passage in your journey

as musicians. To be sure, you should all have

plenty of fuel to feed the fire that is your

intellect but NEVER forget that instinct and

unbridled emotion are critical elements of beautiful,

dramatic and engaging music. For two years we

have forged a connection between your mind and

your ear. As you move forward, never deny your

soul a place in that union.

Congratulations!

Professor Andy Brick

|